Two all-beef patties that can kill.

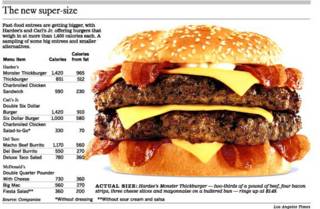

Today's LAT both thrills and offends readers with a prominent article on Hardee's new Monster hamburger, a colossal creation, "Loaded with two 1/3-pound Angus beef patties, four strips of bacon and three slices of cheese, slathered with a generous glob of mayonnaise and encased in a buttered bun."

The public policy debate over food portion sizes, diet, and overweight Americans has echoed many of the same themes over the decades, many of them conflicting: Americans are slothful and obsessed with fat food; Americans want healthy food but fast food outlets won't give it to them; Americans are savvy consumers of fast food and get a higher marginal return of calories for little extra cash with "super sized" meals, etc.

Today's article raises another angle; namely, that a core segment of the fast-food market - young, single men - actively participate in cultivating their own masculine culinary culture by eschewing healthy portions and menu items:

The Monster has been singled out — the Center for Science in the Public Interest called it the "fast-food equivalent of a snuff film" — but the $5.49 4-inch-tall sandwich is just the latest in a heart-clogging trend.

Big is nothing new at fast-food restaurants. McDonald's, for instance, famously offered Super Size fries and drinks until it overhauled its menu to promote a "balanced lifestyle" in March — coincidentally, or perhaps not, after the gross-me-out documentary "Super Size Me" premiered at the Sundance Film Festival.

But the newest trend isn't just about size or value. It's about thumbing your nose at the food police.

Hardee's has received fan mail from people grateful for the guilty pleasure of the Monster Thickburger (about the equivalent in calories of two Big Macs and a strawberry sundae at McDonald's) and offended that health watchdogs would want to take it away from them.

"While other restaurants were a bunch of Nancy-boys and became low-carb cowards in the face of moronic 'they made me fat' lawsuits, you did the AMERICAN thing," John Frensley, a 22-year-old college student from Texas, wrote in an e-mail, "by spitting in the face of lawyers, nutritionists and food-nazi types and offering a monument to Americanism."

This may be helpful in explaining why a certain segment of a consuming public readily adopts trends, even if they are unhealthful (think of the prominent discourse and marketing campaigns with regard to steak houses, cigars, and martinis, which have once again become popular even as Americans exercise more, fewer smoke, and hard liquor consumption continues to decrease), but it really doesn't get at long-term trends.

A historical look at food trends points to a "size creep" towards larger portions, calories, and serving container sizes. The American Dietetic Association found that some of the more popular American food items increased in size dramatically over the 20th century from when they were first introduced:

A Hershey's Milk chocolate bar weighed in at 0.6oz in 1908 and now the bar sizes are 1.6, 2.6, 4, 7, 8oz

Burger King French fries - in 1954 2.6oz was described as Regular. Now 2.6 is described as Small, 4.1 Medium, 5.7 Large and 6.9oz King.

Similarly, McDonald's French fries weighed in at 2.4oz in 1955. Now 2.4oz are Small, 5.3 Medium, 6.3 Large and 7.1oz Supersize.

Hamburger sandwich at Burger King weighed in at 3.9oz in 1954. Now is it 4.4oz (Hamburger), 6.0 (Whopper Jr.), 6.1 (Double Hamburger), 9.9 (Whopper), 12.6 (Double Whopper).

McDonald's Soda, from fountain - in 1955 it was 7fl oz, now the sizes are 12fl oz (Child), 16 (Small), 21 (Medium), 32 (Large), 42 (Supersize) 7-Eleven

Coca Cola, in 1916 the original bottle contained 6.5fl oz now bottles or cans come in sizes of 8fl oz, 12, 20, and 34fl oz.

In 2003 JAMA published a research article on trends in food portion sizes from 1977-1998, which found an overall increase in portion size both in the home and at fast food establishments:

Portion sizes vary by food source, with the largest portions consumed at fast food establishments and the smallest at other restaurants. Between 1977 and 1996, food portion sizes increased both inside and outside the home for all categories except pizza. The energy intake and portion size of salty snacks increased by 93 kcal (from 1.0 to 1.6 oz [28.4 to 45.4 g]), soft drinks by 49 kcal (13.1 to 19.9 fl oz [387.4 to 588.4 mL]), hamburgers by 97 kcal (5.7 to 7.0 oz [161.6 to 198.4 g]), french fries by 68 kcal (3.1 to 3.6 oz [87.9 to 102.1 g]), and Mexican food by 133 kcal (6.3 to 8.0 oz [178.6 to 226.8 g]).

And MSNBC reported on academic studies showing that consumer really did eat what's on their plate, meaning that, coupled with marketing campaigns emphasizing larger portions, customers would consume more calories over time, with little awareness, save for the extra clothing sizes:

In one study -– which Rolls believes to be the first academic research to examine portions in a restaurant, not a lab -- she and her team served an average portion of a baked pasta dish, along with one that was 50 percent larger. The entrees were served in the same sized dish but on different days, so both would appear the same and diners would have no basis to compare them.

When served the regular entrée, people ate an average 399 calories worth of pasta; those who ate the larger portion consumed an average 571 calories, according to the study, published in the March edition of the journal Obesity Research.

Surprisingly, when eating the larger portion, diners also ate more accompanying side dishes, and tacked an average 159 extra calories onto their meals. Rather than their stomachs accommodating the outsized entrée by eating less of everything else, or eating less during another meal, they simply absorbed the extra calories.

The same marketing journals that discuss "super sized" food portions trends also point to "light and healthy" meals as a new marketing segment, and the same fast food firms that are creating killer burgers are also selling low-fat alternatives, salads, and putatively "healthy" fare. How to account for the popularity of both, apart from an increasingly divergent consumer base (red food/blue food states)?

During a recent phone call to a friend I was asked whether I had made any New Year's resolutions. I hadn't, but his question pointed to a peculiar aspect of American culture, in all its variations, that I think relates to food. We are deeply conflicted consumers, especially of food, given that we relish fatty fast food (an empirical observation born of the data) and at the same time worry about our health, trying on new diets and health kicks as if seasonal fashion (also an empirical observation born of the data - just look at the Atkins craze, including "low-carb pasta" for God's sake). It reminded me deeply of conflicted Protestant culture, prone to excess but rife with guilt, making amends for the weaknesses of the world to which you succumbed. Hence, during Prohibition we also had one of the greatest decades of social and cultural excess ("The Roaring 20s").

The recent rash of New Year's-related articles on dieting point to the tendency for dieters to rebound, gaining their weight back after a few months of trying. In a similar sense, the American consumer as a whole is rebounding, drifting towards healthy habits and food, then gravitating towards larger portions, which - it can't be denied with the data - do resonate with customers.

Obviously, diet control is multivariate and complex; individual choices must be made within the context of historical trends, public health policy, food traditions, and corporate marketing campaigns. But people also exhibit behaviors which I think lends itself to the "internally conflicted" view of the fast food consumer. Years ago a friend visited Los Angeles after many years of living in Seattle where he had become a vegetarian. Upon driving by an In-N-Out hamburger stand, he broke down and had a Double-Double, "Just for old times' sake."

No comments:

Post a Comment